Richard Leitsch was the president of Mattachine Society of New York from 1965 to 1969, and often, when writing to the New York Civil Liberties Union about the right to post signs, or to the U.S. Army requesting its policies regarding homosexuals, he would address his letters to “Gentlemen” and close with “Dick Leitsch,” or a swoopy “DL.”

The Mattachine Society was an organization of homosexual men who fought for their rights before the modern gay rights movement really began. Founded in Los Angeles in 1950, and later creating chapters in New York City and across the United States, the group’s goal was to prove that homosexuals were not abnormal and therefore deserved rights. The documents cited here are from Leitsch’s Mattachine Society papers in the New York Public Library Archives, a collection that contains letters and meeting notes documenting the early efforts for gay rights in the United States. When the Stonewall Rebellion took place in 1969, the nascent gay rights effort in which the Mattachine Society had played a crucial role in took a sharp turn, creating a new, modernized movement.

On April 21, 1966, Leitsch staged what was later called the “Sip In” at Julius’ Bar in Greenwich Village. It was modeled after the sit-ins used in the civil rights movement to protest racial segregation in restaurants. Leitsch, with two other members of Mattachine, visited bars in lower Manhattan and announced to the bartenders that they were homosexuals to test whether they would be served. At the time, it was common for bars to refuse service to gay men, because the State Liquor Association (SLA) was known to take away liquor licenses for serving the “disorderly,” a category in which it included homosexuals. Leitsch and his colleagues brought journalists from The New York Times and the Village Voice along to document their experiment. At Julius’ bar, which was already under scrutiny for other illicit behavior, Village Voice photographer Fred McDarrah captured the bartender putting his hand over the drinks he had prepared for the men, telling them that he thought it was illegal to serve homosexuals.

The sip-in served a pivotal role in Leitsch’s advocacy to end refusal of service to gays in New York bars. In a letter written in March 1967, Leitsch called the Mattachine Society’s activism “amazing.” He said:

I use the adjective “amazing” because it is rare that an organization with no paid staff, existing on volunteer donations, and leading a hand-to-mouth financial existence, achieves anything at all.

We try to serve all homosexuals, be they members of MSNY [Mattachine Society of New York] or not. For example, rather than set up a private club so our members would have a place of sociability, we held a sip-in and fought court cases so that all homosexuals could socialize anywhere with impunity.

Leitsch and his colleague’s efforts to push back against homophobic practices were bold at the time, but the organization’s original goals emphasized staying in line. The membership pledge written in 1951 included:

I pledge myself… to try to observe the generally accepted social rules of dignity and propriety at all times… in my conduct, attire, and speech.

This pledge is in line with the general conformist attitude of the early gay rights movement. At the time, many members of the society were afraid to be out. The name Mattachine did not include “gay” for a reason. Dick, however, was courageously and publicly out. Yet he still sported the neat, suited respectability preached in the pledge.

On June 28, 1969, the Stonewall riots began. The Stonewall Inn was operated by the Mafia, like many of the bars popular among gay people in New York City. Police raids were common among gay bars, but this one was different. The Stonewall clientele tended to be the more marginalized homosexuals, such as youth who lived on the streets and the transgender people who were known as drag queens, and they, along with other local gays, were ready to rebel. A police raid at Stonewall set off riots, which in turn inspired a new and shame-free movement, redefining what was considered bold in gay activism.

During the Stonewall riots, New York Mayor John Lindsay asked Leitsch to put them to an end. Leitsch and Lindsay knew one another from previous negotiations to protect gays from discrimination in the city. Leitsch said, “Even if I could, I wouldn’t… I’ve been trying for years for something like this to happen.” Leitsch later famously said that no one was gay before the 1969 Stonewall riots in New York, and everyone was gay afterward.

Yet the very kind of gay activism that sprouted from the Stonewall riots directly challenged the conformist approach of Leitsch’s Mattachine Society. Following Stonewall, the Gay Liberation Front was founded, and one of the founding members Martha Shelley told me that Mattachine lost many of its members in this process.

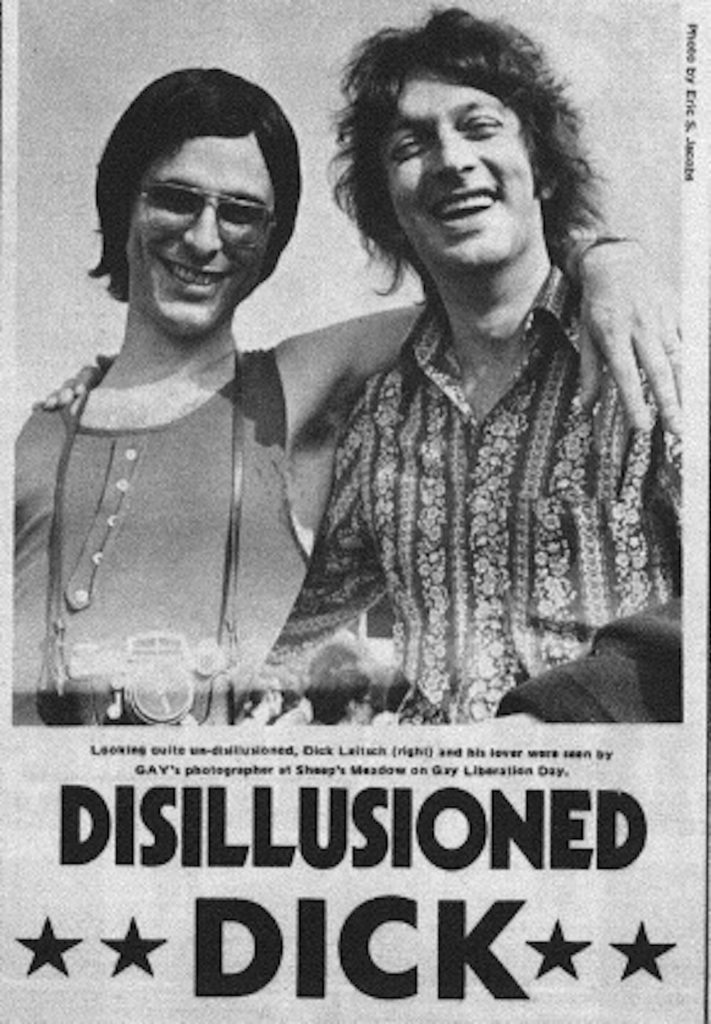

Only a few years after Stonewall, on August 2nd, 1971, Leitsch criticized the gay liberation movement in Gay newspaper. He said that people were inventing reasons to claim being oppressed in order to continue the movement. He referenced a Time article that calls poverty an industry that perpetuates its own existence and said that gay liberation, like poverty, is becoming an industry. He specifically called out Martha Shelley in his piece.

Leitsch’s words in 1971 reflect his consistent stance since even before he became president of Mattachine. A letter written on December 9, 1964, missing the signature but probably from Leitsch, says:

Randy, let me explain something to you. I’m afraid you often get the impression that I’m what Craig would call a ‘phoney liberal.’ Believe me, I’m not. I’m as much an idealist as anyone, but I’ve been shown the impossibility of gaining any Utopia, or even anything like an Utopia in a lifetime, or a generation. Consequently I function as a pragmatist and try to chip away at the established policies toward homosexuals, rather than explode them.

Whether from Leitsch or one of his colleagues, this letter shows the Mattachine attitude pre-Stonewall was much less aggressive than the movement that was born from the riots. The new organizations clearly had “gay” in their titles and staged more public actions without regulations fitting them to heterosexual standards. The post-Stonewall movement was not interested in chipping away, but rather picking up bricks and smashing them into windows.

Shelley says that Leitsch didn’t like her because her work organizing the Gay Liberation Front put his organization out of business, but Leitsch said years later that the Mattachine Society’s goal was to no longer need a Mattachine Society.

Perhaps Leitsch had trouble understanding the broadness of the demands of the gay liberation movement when he saw drastic shifts in gay rights during his lifetime. He joined the movement when members had to pledge to not act flamboyantly in public and be the utmost respectable so they could be taken seriously. The Stonewall uprising created a movement that rambunctiously took Mattachine’s fantasies and turned them into demands, and more demands. Leitsch’s accounts show that he clearly admired the Stonewall uprising, but his comments later show that he may have seen it as a finish line while others saw it just as a beginning.